The important thing to understand about Jacobs' thesis is that she believes too-quiet streets are boring, unsafe, and an economic bust: "On successful city streets, people must appear at different times."

The important thing to understand about Jacobs' thesis is that she believes too-quiet streets are boring, unsafe, and an economic bust: "On successful city streets, people must appear at different times."She explained this in "social terms while discussing street safety and neighborhood parks" and now in chapter 8 "On Mixed Primary Uses" turns to its economic effects.

Multiple Uses Create Synergies

She notes that residents on a street and nearby streets can support "a modicum of commerce" by themselves. People who do not live nearby, but who work in the area, support an additional amount of commerce. She says that "we support these things together by unconsciously cooperating economically." Enterprises would not be able to thrive based on residential trade or commercial trade alone are able to thrive when these two populations combine. "As it is, workers and residents together are able to produce more than the sum of our two parts."

No neighborhood or district, no matter how well established, prestigious or well-heeled, and no matter how intensely populated for one purpose, can flout the necessity for spreading people through time of day without frustrating its potential for generating diversity. Furthermore, a neighborhood or district perfectly calculated, it seems, to fill one function, whether work or any other, and with everything ostensibly necessary to that function, cannot actually provide what is necessary if it is confined to that one function.

Daily Totals and Hourly Distribution are Distinct Matters

She draws a distinction between total daily numbers and their distribution. "Sheer numbers of people using city streets, and the way those people are spread through the hours of the day, are two different matters."

As we have had occasion to mention several times, the Capitol Mall and Civic Center are two instances where large numbers of people are insufficiently distributed because of single use and monoculture.

Even in downtown Salem, and even if the new condos and other new housing were fully sold, the numbers of people would be still too small to make a difference. More is necessary!

Waterfronts as Resource

Jacobs also notes that "the waterfront itself is the first wasted asset capable of drawing people at leisure." She thinks big. "Part of the district's waterfront should become a great maritime museum." She also calls for restaurants, tour boats, and other attractions. And she says that "there should be related attractions, set not at the shoreline itself but inland a little, within the matrix of the streets, deliberately to carry visitors farther in easy steps."

Front Street and Oregon Electric Rail Line together act as a moat that divides downtown from Riverfront Park. It's hard to get there, and there's a reason people drive cars to it so often. Front street also is not lined with business that draw traffic from the park or send people to the park. That matrix is entirely missing.

"CBDs" Embody Functional Analysis and Blight

She derides "central business districts" as "duds." "Most big-city downtowns fulfill - or in the past did fulfill - all four of the necessary conditions for generating diversity. That is why they were able to become downtowns. Today, typically, they still do fulfill three of the conditions. But they have become too predominantly devoted to work and contain too few people after working hours. This condition has been more or less formalized in planning jargon [as the cbd]."

Vitality, Diversity and the City's Need for the Profane

Salem wants vitality without diversity. Jacobs answers that without diversity, there is no vitality.

This is why projects such as cultural or civic centers, besides being woefully unbalanced themselves as a rule, are tragic in their effects on their cities. They isolate uses - and too often intensive night uses too - from the parts of cities that must have them or sicken....

American downtowns are not declining mysteriously, because they are anachronisms, nor because their users have been drained away by automobiles. They are being witlessly murdered, in good part by deliberate policies of sorting out leisure uses from work uses, under the misapprehension that this is orderly city planning.

Jacobs goes on to discuss the San Francisco Civic Center, a development strikingly similar to Salem's Civic Center in the larger Pringle Creek Urban Renewal Zone, as well as the Capitol Mall area. Fortunately we haven't had the same level of blight, but both areas suffer from a decided lack of vitality and diversity:

Fourty-five years ago, San Francisco began building a civic center, which has given trouble ever since. This particular center, placed near the downtown and intended to pull the downtown toward it, has of course repelled vitality and gathered around itself instead the blight that typically surrounds these dead and artificial places. The center includes, among the other arbitrary objects in its parks, the opera house, the city hall, the public library, and various other municipal offices.

Jacobs concludes that "Every city primary use, whether it comes in monumental and special guise or not, needs its intimate matrix of "profane" city to work to best advantage." She calls this "jumbles to the simple-minded" and contrasts it with the "profane monotony" like housing projects and a "sacred monotony" like civic centers. (italics added)

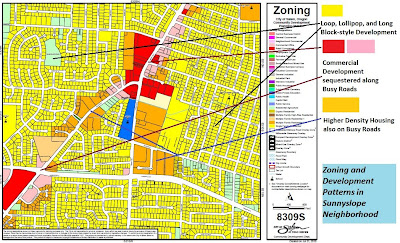

(City of Salem Zoning Map 8309S, with annotations - click to enlarge)

Residential Areas also Need Mixture

She also notes that residential areas need diversity.

Residential districts lacking mixture with work do not fare well in cities....Perhaps more than anything in Salem, the suburban style expanses of "quiet" residential neighborhoods yield monotony and dullness.

Most city residential districts also have blocks that are too large, or they were built up all at once and have never overcome this original handicap even as their buildings have aged, or very commonly they lack sufficient population in sheer numbers. IN short, they are deficient in several of the four conditions for generating diversity.

Here we have an example from the Sunnyside neighborhood, which we discussed earlier in some comments. It shows perfectly the ways that neighborhoods structured to be far from economic generators of diversity, and essentially to require automobiles and to hinder walking or bicycling.

Salem is working on some new mixed-use zoning codes, but it's not clear how robust these will in fact be.

(Next up: Small blocks)

1 comment:

Walker adds via email:

The thing about Salem's proposed NCMU is that it's becoming clear that it's just a way for the camel's nose of strip-mall sprawl to penetrate residential.

The real mixed use that people like is accomplished by taming the auto and restricting it, not catering to it. The way to create real, neighborhood friendly commercial businesses is to restrict severely the parking -- parking maximums rather than minimums etc.

Having lived in cities and small towns that developed pre-zoning and pre-auto-domination, I can clearly distinguish a true neighborhood business from the BS that the city is trying to polish under the name "neighborhood commercial" -- a true neighborhood business can thrive with two parking spaces, tops, and depends primarily on people FROM A NEIGHBORHOOD (hence the name) walking or biking over, or stopping by as they walk to and from the bus.

The concept being prepared under the NCMU zone proposal is nothing like this and is intended only to destroy the ability of neighborhoods to protect themselves from undesirable commercial encroachments. The only way to prevent the destruction of residential areas by this plastic version of mixed use is to

1) Allow more retail/walk-in/drop-in businesses in residential areas (pubs, corner stores, tailor shops, news-stands)

BUT

2) DON'T allow commercial parking -- instead, limit the parking to the standard suitable for the RESIDENTIAL part of the mixed use picture. That way, the area is protected from the drive-throughs, etc.

Post a Comment