Over at Sightline they've got a new piece that is interesting. In "Yes, Oregon, There Is a Way to Build Enough Homes" they look at the housing production in the 1970s, and suggest that widespread downzoning in the 1970s was one ingredient in the decline in housing production.

Multifamily construction in Oregon soared in the 1970s, plummeted in 1980, and has never recovered. By the 2010s, the share of net new Oregon homes in multifamily buildings hit its lowest average in 60 years.

In part, that’s because the public backlash against what former Governor Tom McCall had called “coastal condomania” had also reached far inland. For example, as part of a national trend in the ‘70s, a major downzone banned apartments from much of inner southeast Portland.

We've touched on the rise and fall of construction before here, most recently on last year's Council Work Session on housing.

|

| We are currently underbuilding homes (Oregon Office of Economic Analysis) |

There is some evidence for increasing downzoning here in Salem also.

This will just be a glancing, impressionistic survey, and there are many questions to follow up on in more detail. There are overlapping debates that could have led to downzoning, and not all the downzoning was aimed at banning apartments in the city. A lot of the discussion in the papers about downzoning concerns rural land and County planning, zoning, and land use decisions. It looks like the County had to approve the City's plans, and that

appears to have been unwound in today's regulatory scheme, for example. Any good history of 1970s action will also require more knowledge of land use law itself, of SB 100 and the early DLCD, of County-City relations, and of City planning documents. Since this remains in living memory for some, you may know more about one or more of these!

Just at the city level, the adoption in late 1974 of new Statewide Planning Goals arising out of SB 100 and the development of Neighborhood Associations, together seemed to trigger new interest in downzoning. There was also was a recession around 1980 and so it is important to say the downzoning was but one ingredient in any decline in housing production, and not the only factor. (The Sightline piece discusses a couple other factors, too. There are multiple variables in play here and, again, this is merely a sketch.)

The Comprehensive Plan Map was not always Aligned with the Zoning Map

The 1973 Comprehensive Plan described "rapid production" of apartments. Interestingly it did not "distinguish between Single-Family and Multi-Family Residential areas" and talks at least in passing about a "mixture of residential with other uses in and near the core area and along major arterial streets." This may represent a course-correction from the 1963 Plan, which employed "buffer zones" between single detached housing and commercial zones. Any shifting extent for sort-and-separate zoning is not clear. The 1973 Plan and zoning map deserve a closer reading.

|

| On housing in the 1973 Comp. Plan |

But the Comprehensive Plan soon came under fire. In 1975 it was in the news.

|

| September 24th, 1975 |

The Comprehensive map had developed somewhat independently of the zoning map. It seemed to be conceptualized that the Comprehensive map faced forward, long range, and the zoning map represented near- and medium-term arrangements. So there were swaths of Salem where the Comprehensive Plan designation did not align with the zoning, and this became a problem after an Oregon Supreme Court decision, Baker v. City of Milwaukie in 1975.

|

| November 26th, 1975, morning |

|

| November 16th, 1975, afternoon |

There is more to do on understanding what really is going on in this debate:

A Salem realtor...accused city government of using the recent Oregon Supreme Court Baker vs. Milwaukie decision "as a crutch" to downzone commercially zoned property.

In that map clip, much of the shaded land in dispute is along rail and highway, and includes places like the Fairview industrial area and does not seem to overlap much with any areas that today have low-density residential zoning. It's not clear that banning apartments for single detached housing was at all central to this instance of downzoning.

Localized Instances of Downzoning for Residential Land

But even before the general criticism of the Comprehensive Plan, there were other instances of downzoning. There is evidence for smaller kinds of neighborhood-level spot downzoning distinct from any citywide effort.

And here are a couple of familiar names early in their careers!

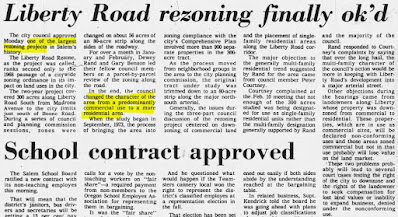

in a 1975 article on zoning around Liberty Road, journalist Chuck Bennett wrote about City Councilor Peter Courtney, that he "voted consistently against the multi-family uses" and "complained that not enough of the 300 acres is being designated for use as single-family residential units rather than the multi-family designation...." In round terms, 300 acres is about the size of the Fairview redevelopment.

|

| Chuck Bennett and Peter Courtney February 11th, 1975 |

It took a while, and a few months later Council "changed the character of the area from a predominantly commercial use to a more residential use."

|

| July 15th, 1975 |

Other Moments in the Downzoning Discourse

In the conversations and debates around downzoning, developers objected to it as a form of "takings," a subtraction of value from land. Residents of detached single housing, again, wanted downzoning to "protect neighborhood character."

Different notions of what constituted a "taking" or devaluing might be interesting to look at another time, as I am not sure they have been stable over time. I think there is some shifting, and the meaning may not have stabilized until Dolan v. City of Tigard in 1994.

There were also editorials on downzoning.

|

| February 23rd, 1976 |

Even though this editorial was about California, its central example framed the matter and pointed out

that "a property with a commercial or industrial zoning designation if

far more valuable...than single family residential zoning."

Some explicitly linked downzoning to our great land use law SB 100, and talked about downzoning too much "commercial land as residential." It's not clear at the moment if this should be understood as implying single detached residential housing or residential more generally.

|

| March 17th, 1976 |

Neighborhood Associations also started at this time, and they deserve more attention, a critical history that looks at both their positive and negative influence. They appear to have supported more downzoning.

The Mayor's race in 1976 also looks like it is worth a closer look. Here's a letter to the editor that frames the race as a partial referendum on downzoning.

|

| May 21st, 1976 |

Nevertheless, They Knew we needed Housing

Sometimes statements about needing housing are understood as expressions

of developer greed, but maybe we need to start reading them as accurate

assessments of housing markets and population.

|

| December 4th, 1975 |

On a superficial level, from this survey it appears that the primary frame for discussing downzoning was usually impacts to individual property owners and prospects for loss of value, and not necessarily "protecting neighborhood character." Nor is very much discussion of citywide or regional impacts to housing supply and housing cost. (See that Letter to the Editor above, which stresses loss of value.)

Yet here's a clip from a large, multi-page spread on mobile homes. It leads with "the average Oregon family can't afford the average new home." It rings with so many themes that continue to echo today.

|

| November 16th, 1976 |

And look! There is an instance of a classic Strong Towns argument: "the tax revenue per acre in a mobile home park is actually greater than that in other residential areas."

Identifying all the players, their preferred policies, their biases, and the politics of it all is not possible at the moment. Again, hopefully there will be more to say another time.

But at least in a preliminary way, it does appear there was some downzoning that resulted in banning apartments in a greater proportion of Salem in the 1970s.

No comments:

Post a Comment