It's Black History Month and Macy's is closing.

It's a good time to revisit the "Colored School" in Little Central located on the corner of Marion and High Streets, the north side of the Macy's block.

|

| Little Central, home for "Colored School" on Marion at High (Streetview in 2012, State Library inset) |

There's nothing really new here, but maybe we can refine a few details.

In her recent book, The Rise and Fall of the Second American Republic: Reconstruction, 1860-1920, Manesha Sinha focuses on Black self-determination as she stresses bottom-up action in "grassroots Reconstruction" and "Black Reconstruction." On education she writes

In 1865, the Freedmen's Bureau ran 740 schools with 90,589 students and 1,314 teachers....This was a "drop in the bucket," though, as the Bureau received hundreds of applications for new schools from freedpeople....As a result of congressional appropriations during Reconstruction, the Bureau schools were put on a firmer footing. But the biggest driver of the educational success of the Bureau remained freedpeople themselves. By 1867, "colored pupils" were paying school tuition and freed people contributed considerably to the upkeep of freedmen's schools....Freedpeople's desire for education transcended age; many adults started "self-teaching." Freedpeople established their own schools in "cellars, sheds, or the corner of a negro meeting house"....

Our establishment histories haven't said much about the Colored School here, in part because little was known. As I read it, pretty much everything depends on and is a refinement of Sue Bell's 2002 piece in Historic Marion and later adapted for her Oregon Encyclopedia piece, "Salem's Colored School and Little Central."

The Salem Online History, now hosted at the Mill, discussed it in the context of Black History more generally.In 1867, the African American community in Salem raised $427.50, which allowed them to operate a school for six months. They placed an announcement in the newspaper, saying that “Notice is hereby given that the colored people of Salem expect to pay all the expenses of the Evening School now being held by them, without aid from other citizens – no person is authorized to collect funds in our name.” The following year, the city of Salem continued what they had begun, and opened Little Central School. This segregated school was located near Central School on High Street between Center and Marion. Its fifteen minority students were taught by Marie Smith and Mrs. R. Mallory. Tuition at Little Central was $4 a term, the same that white children paid to attend “big” Central School.

And reference in the Mill's piece on Emancipation celebrations:

the African American community of Salem was renting a room in order to have a school that their children could attend, the city’s schools having barred their children entry (even though they were paying the taxes that supported the city’s school system). Fed up, parents raised enough money to hire a teacher and rent a room to provide their children with an education.

Sinha's notes on history and self-determination suggest a broader reading of the Colored School as an expression of Reconstruction here in Salem. It was not just a local story but took place in that national context, and also would offer more evidence that Reconstruction was story for a much wider area than the South.

There is some evidence that locals understood it this broader way.

In a February piece from 1868 full of vile, racist language (bowdlerized here with brackets), the Albany State Rights Democrat quotes the Oregonian:The colored people of Salem give notice that "they expect to pay all the expenses of the Evening School now being held by them, without aid of other citizens. No person is authorized to collect funds in their name."... In Democratic patois, "[the colored people] are getting sassy."It directly linked the Salem school and the politics of local education with national themes.

What we oppose is the proposition sometimes advocated...to have [colored children] go to the same school with white children. We also oppose the [Freedmen's] Bureau because it wrings from the white men of the country from twenty to thirty millions of dollars annually to feed, clothe, educate and pamper worthless lazy [people]....

As for Salem, there appear to be two separate school sessions that are getting a little squishy sometimes. As I read it, there was first a daytime school for kids and then evening school for adults. The quotes about "expecting to pay" and " no person is authorized to collect funds" appear to be about the evening school, not the first daytime school. It's not possible to be certain at the moment, however.

Bell located the origin with William P. Johnson.

African American artist William P. Johnson had offered in 1861 a scholarship of $500 to one of the schools to allow his daughter-in-law to enroll, but his offer had been rejected. By March 1867, he had collected enough funds from friends and other Black families in Salem to open a school with about eight students and possibly some young adults. With $430.75 in hand, he rented a room for $10 a month and engaged a teacher to conduct classes.

If we can find it, there is surely more to say about Johnson!

|

| March 13th, 1865 |

|

| July 17th, 1872 |

He might have been more primarily a tradesman than artist, but that could have been a day job also to support his art. The list of references in his ad were leading Salemites. His obituary says he "commanded the respect of all who knew him" and that "he had amassed quite a snug little fortune." I read this as mainly sincere rather than patronizing.

We may never know much about the fund-raising for the school. An Albany notice from January 1867 suggests the money was in hand already. Maybe it was mostly Johnson's, or maybe there was a much broader distribution of contributions. Discussion and planning and soliciting must have been going on for a while, invisible to most white people.

|

| January 26th, 1867 Albany State Rights Democrat |

In 1867 a March start date for the school seems about right. This Oregon City note from September said it's been going for six months.

|

| September 21st, 1867 Oregon City Enterprise |

Of course $400 is not a trivial sum, and Johnson's ability to have it in 1861 or in 1867 indeed testifies to some actual wealth. Here's a clip from a list of building projects between January 1865 and January 1866.

|

| March 5th, 1866 |

Ordinary shops and homes could be built for $400. That's a significant amount to raise from a small number of people.

Interestingly, Daniel Jones shows up for his barbershop. This has to be Rev. Daniel Jones before he was ordained! The Mill's history says he was in Salem "by 1868" and a note on last year's Juneteenth walk says his barbershop dates from "about 1866." We can push his arrival back a little more into the calendar year of 1865. He's also not racially tagged with "colored." Later accounts called him a "teacher" and he may have taught at the school also.

|

| August 28th, 1865 |

Additionally, the mechanism of school funding might deserve more attention.

Bell said

Even though the 1862 Oregon Code of Laws required that schools be free to all students “between the ages of four and twenty years,” the children of African American residents—seventeen in the 1860 census and fifty by 1870—continued to be excluded from attending the city’s public schools. Their parents, however, were required to pay the five-mill (5/10 of a penny) school assessment tax imposed by the school district.But this does not seem like the best way to describe the funding. Here's a piece from a few years later. It was on a proposal that would provide funding for free schools, one of which would be the colored school. For whatever reasons, between 1862-1871 schools here for both Black people and white people were not "free."

|

| April 26th, 1871 |

There were two other articles on free school in the same issue of the Weekly Statesman. It was a debate.

A few years later in 1887 the paper rehearsed the history and said it was more than a polite debate and called it "stormy time."

|

| January 7th, 1887 |

This piece from 1951 also references the 1871 property tax and suggests we understand it as a rough capital/operations budget split.

|

| March 28th, 1951 |

Until that moment in April of 1871 there was that five mill property tax, which Black Salemites had indeed been paying. But it was for buildings, and roughly seems to have been for the capital expense. The tuition fees paid the operations/staffing budget for teachers. Despite the 1862 law Bell cites, white families also had to pay tuition until the 1871 decision for "free schools" and a bump up in the property tax rate.

The first 1871 clip had said that Lucy Mallory's husband, Rufus, was on the School Board. She taught in the Colored School.

|

| January 7th, 1887 |

This second clip form 1871 gave approximate construction dates. Big Central was apparently completed in 1858. Little Central and the first East School (with which Big Central has been confused in photo captions - see notes below for a link to a more detailed discussion) completed between 1866 and 1869.

|

| At the OE, reproducing an errant photo ID This is the first East School and later than 1863 |

It has seemed that Little Central was originally constructed as overflow, and not originally intended to be the Colored School. But the need for overflow didn't quite materialize, and the building became available for Black students. To say, as the online history piece now at the Mill does, that "the city of Salem continued what [the Black families] had begun, and opened Little Central School" may be a little misleading and optimistic about intent. (More certainty on this might surface with new evidence.)

The piece at the Mill says Marie Smith was a teacher in addition to Lucy Mallory. Here's a reference to Maggie Patton, also, teaching the evening classes for adults.

|

| February 7th, 1872 |

Little has turned up on Marie Smith or Maggie Patton, and another time there might be more to say about them.

This work on education, even segregated as it was, along with organizing for woman suffrage and spiritualism in the early 1870s, has suggested that there were currents in Salem that can be understood also in the national context of Reconstruction.

|

| March 30th, 1877 |

This reception for the Tennessee Jubilee Singers, hosted by George Williams, is ambiguous. You will recall "Major" George Williams, later banker and Mayor, and if this is the same person, this is evidence for social mixing that became more difficult in later decades. The singers also did not seem to have trouble with any hotel accommodations, which also became difficult or impossible in those same later decades. Recall the famous story about Mark Hatfield driving Marian Anderson (and others) to Portland for the night.

Still, as Bell notes, the census offers evidence that Blacks left Salem between 1870 and 1880, going from about 60 to only 16. This drain says something also.

|

| Jeremy Okai Davis at Bush Barn right now (via Elizabeth Leach) |

See also:

- "Lucy Rose Mallory: Publisher, Feminist, and Spiritualist" (2020)

- "With New High School, Big Central School was Moved in 1906" (2020 and 2023) Because of an error in a photo ID and caption in the Salem Library Historic Photos, this had be substantially revised in an addendum, and the second half is the relevant part. (The Oregon Encyclopedia article on "Salem's Colored School and Little Central" also reproduces the errant photo ID and shows the first East School rather than Big Central.)

- "Notes on Black Churches in the 19th and early 20th Century" (2022)

- "Which George Williams was Mayor and Banker here?" (2024)

- Not directly related, and not showing Daniel Jones or William Johnson, Elizabeth Leach Gallery has a nice note on the current show at Bush Barn, "ReEnvisioned: Contemporary Portraits of Our Black Ancestors."

Addendum

William Johnson, his family, and home may have been the center of community for Black Salemites.

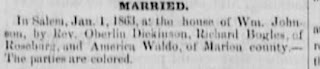

Over at the Shineonsalem historical digest for 1863, it says "Richard and America Waldo Bogle were married at the First Congregational Church on January 1."

But a newspaper notice says they were married at William Johnson's house.

|

| January 12th, 1863 |

|

| Unsigned letter to Mary Denison Lyman (Pacific University) |

A contemporary letter dated January 25th, 1863 from an unknown white person (Daniel Waldo's wife, Malinda, perhaps, since she had lived with them?) and sent to Mary Denison Lyman, confirms this, saying:

I suppose you will wish to hear the news that is afloat in this direct -- Well the first thing that took entire possession of the people of Salem in 1863, was a few white ladies attending America Waldo's wedding held at the house of W. Johnson (colored). America lived with us & was the best girl we have ever had in the family. She was very anxious that the ladies in whose families she had lived should see her married, accordingly a hack was sent around on New Years & gathered in her numerous friends for all who knew America could not help loving her [even] if she was half black.

The Secretary of State's piece on the Waldo-Bogle family reproduces Rev. Obed Dickenson's wedding certificate for them that names William Johnson as a witness.

Later that same year, at least for a time, Eliza Gorman, daughter of Hannah, ran her dressmaking business from the Johnson's. (See also on brother Hiram Gorman, who came to Salem later.)

|

| December 28th, 1863 |

About 1870 Johnson lived on the northwest corner of Marion and Church, not even a full block from Little Central, and directly across the street from Big Central.

|

| Salem Directory for 1871 |

On the Bayless family 2023 Juneteenth walk map, the Mill notes another instance of witnessing a marriage:

Mary Ann Reynolds and Albert Bayless were married on October 28, 1866 at the home of Dan Jones. The 1867 Salem City Directory lists Dan Jones as residing on the Northwest corner of High and Mill Streets. The wedding was witnessed by Elizabeth and William Johnson and preformed by Rev. Obed Dickinson.On the Daniel Jones 2024 Juneteenth walk map, the Mill notes "the Salem City directory for 1872 lists Rev. Daniel Jones as residing at the corner of Marion and Winter Streets."

So Marion Street may have been a center for Black families c.1870, possibly anchored by William Johnson and Little Central.

There remains so much to learn.

Addendum 2, February 4th

Here's a possible explanation for calling Johnson an "artist." There were two W. P. Johnsons! That would be an easy confusion. This one advertised himself as an "artist," but also was white, and related by marriage to F. B. Southwick. (See links at findagrave.)

|

| September 20th, 1878 |

|

| January 7th, 1887 |

|

| August 8th, 1919 |

7 comments:

Added more on William P. Johnson

Added some disambiguation on a second William P. Johnson

The letter to Mary Denison Lyman is interesting for its centrist-progressive perspective. While the writer attended the Waldo-Bogle wedding without duress, and even gladly, she [I am assuming she] defended herself from actual or implied criticism, saying that she did not eat at the same table with any Black Salemites. She also thought Rev. Obed Dickinson went too far for Salem. Mixing, but not too much mixing.

"The next day [after the wedding] every busy body in town was spreading the news & made out we had been guilty of great impropriety....

J. Wilson & Mr. Dickinson were all the white men present. No black darkies stood at the table with us & they had an excellent [crossed out: supper] dinner. There has been one piece in the Corvallis Union & another coming out this week in a Eugene paper with the names of the guests present....

There is a great amount of dissatisfaction felt towards [Rev. Obed Dickinson] throughout the whole town & it gets worse every abolition sermon he preaches. He has not been preaching anywhere lately & his church feel[s] anxious that the house is being completed [and] that he should not force those sermons upon the people unless they know the day so they can go elsewhere if they chose....

You may think I am prejudiced but I do really believe a minister against whom there is no such strong prejudices, even if his mind was inferior to Mr. D[ickinson], would do more good here."

It's been over a month, are you still running this blog?

Miss your work and hope that you’re okay and just taking a well-deserved break

Such a meaningful place to revisit—there’s so much history tucked into corners like that. 🏫✨ Thanks for the reminder to slow down and appreciate it. And speaking of good times, if you're in the area early,wendys breakfast prices is totally worth a look—great prices and perfect fuel for a morning of exploring! 🍳🥓

Can this be deleted? We don't need advertisements in the comments section.

Post a Comment