We'll never find out enough about the Gorman family. A few years ago the Corvallis house of Hannah and Eliza Gorman was placed on the National Register. Hannah had come to Oregon as a slave, claimed and gained her freedom, and achieved modest prosperity.

|

| Hannah and Eliza Gorman House, Corvallis National Register of Historic Places Nomination |

The Sunday paper had a small notice about another member of the Gorman family, Hannah's son, Hiram. At Bush Barn on May 15th there will be a lecture titled, "The Statesman and the Freedman: Asahel Bush, Hiram Gorman, and Black Exclusion in Oregon."

A capsule biography gives us an outline,

Hiram was well known in Salem for his beautiful home on the corner of Liberty and Chemeketa streets and his prized vegetable garden. But he was best known for being the operator of the steam powered letter press at the Oregon Statesman. For twelve years, every paper printed by the Statesman passed through Hiram Gorman’s hands.

|

| May 25th, 1877 |

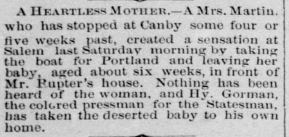

This note about bringing early potatoes to market is striking because it is not racialized. Most of the time Hiram Gorman is tagged in racialized ways, as in this note year later about fostering an abandoned child.*

|

| Oregon City Enterprise, Aug. 15th, 1878 |

Even with that, or in part because of that as a person considered exotic, Hiram Gorman was a known personality. Multiple Oregon papers reprinted news of his death, and several also news of Hannah's death, which had occurred earlier in July, and perhaps accelerated his own illness and death. It is nearly certain he was separated from her involuntarily, and perhaps violently, in the early 1840s, and he was able to reunite with her when he came to Oregon around 1871.

|

| Albany Democrat July 24th, 1888 Oregon Scout, August 10th, 1888 |

|

| In Salem, July 24th, 1888 (via Salem Reporter) |

The lecture will probably focus more on what we can know of Gorman, as a subject and agent in his own life and family. Gorman, and others, were not merely objects acted on or oppressed. Even in constrained circumstances they actively shaped their destinies.

Still, as this project of reassessment moves along, hopefully we won't lose sight also of Asahel

Bush and his legacy, including the newspaper he founded, even after

others purchased it. It is important to "elevate and celebrate" the

stories of those marginalized, but it is also important to understand

more about the scope and mechanism of marginalization. We still need

more history of Bush's banking and investments after he sold the

newspaper. Bush lived for a full half-century after Statehood, and

limiting investigation of his racism to his political and newspaper

activity in the 1850s may still too much function to protect his reputation. There

are structural and institutional things to investigate, not just

attitudinal postures of personal racism publicly expressed.

In this light, here we'll return to the most visible way the story of Hiram Gorman was retold and received by a white readership.

Four years before the two Gormans died, in 1884 RJ Hendricks, aka "the Bitsman," purchased part of the Statesman, and over a full generation later, as he returned to his recollections and writing "bits" of history for his daily column, he wrote many times in the late 1920s, 30s, and 40s about Hiram Gorman. It is, actually, a little odd how he returned over and over to Gorman. There might be something behind that, as the repetition is a little obsessive rather than any kind of iteration with successively improved tellings of history.

|

| December 10, 1930 and April 14th, 1942 |

Hendricks also accented different details, and suggests that Gorman

lost his job when the press went to steam power shortly after the

purchase in 1884. He claimed multiple times that Gorman "was the motive

power" of the press, that it ran on human power, "sweat power," furnished by this "giant negro." He said in 1929,

"Hi, drunk or sober, was the power till the latter part of 1884, when a

steam engine was installed." He stresses that Gorman was the operator

of a manual press, and not the operator of a steam-powered press.

Clearly we have to ask how distorted by racism and othering is this description and this version of history. The focus is on Gorman's bodily capacity, even super-human capacity, as a laborer and former slave. Another theme Hendricks highlights over and over is what might have been a functional alcoholism and PTSD. He also said Gorman could only count to ten, making implied claims about intelligence or education. For Hendricks Gorman was physical force, not a mind and personality.

In the way Hendricks returns to the story, over and over, always with the same details and bias, he obfuscates rather than reveals. There is a kind of erasure to it.

If Hendricks seemingly wanted to minimize the character and significance of Hiram Gorman, in fact the family was pretty-well known and had achieved some level of prosperity. From the National Register Nomination:

The years between 1844 and the mid-1850s are yet somewhat mysterious....By early 1857 (perhaps earlier), four years before the start of the American Civil War, Hannah and Eliza had relocated about 15 miles south to Corvallis and despite the restrictions of the Territory's exclusion laws they began to purchase property. Over the following nine years, between 1857 and 1866, the Gormans purchased in total four city lots....This relative prosperity was reflected in the 1860 census...the Gormans were comfortable and well-respected in the community.

There is much to recover here, but it is unlikely we will ever know a great deal of it.

* See also Virginia Green's piece in Historic Marion, spring 2002, "Hidden Citizens," which has more on the Gormans and the abandoned child.

State Archives also has a note on Hannah and Eliza Gorman, and the Oregon Historic Sites Database links to the initial inventory and subsequent National Register Nomination. Findagrave has Hannah's obituary.

Also, since a theme here on the blog is the way our Historic Preservation framework needs an update, and we have often highlighted the exclusionary function of Historic Districts, which are overused, it is worth pointing out that this individual listing on the National Register is an instance of Historic Preservation working right, preserving a structure while also contributing to a richer, more accurate, and altogether improved historical narrative. We need projects like this, and fewer like the recent district-level project in Grant here in Salem.

No comments:

Post a Comment