As best as I can tell, a small news piece on September 17th, 1918, was the first local mention of the 1918 flu pandemic.

Relative to the headlines for World War I, the notice on the 17th was tiny.

But a week later, on September 23rd, there were other mentions, and it became nearly a daily thing. They did not know of course how it would unfold, the horror and the vast scale of its lethality. The Center for Disease Control notes that it "was so severe that from 1917 to 1918, life expectancy in

the United States fell by about 12 years, to 36.6 years for men and 42.2

years for women."

According to the Center for Disease Control it is not surprising we didn't read much about it earlier in 1918:

In the United States, unusual flu activity was first detected in military camps and some cities during the spring of 1918. For the U.S. and other countries involved in the war, communications about the severity and spread of disease was kept quiet as officials were concerned about keeping up public morale, and not giving away information about illness among soldiers during wartime. These spring outbreaks are now considered a “first wave” of the pandemic; illness was limited and much milder than would be observed during the two waves that followed.

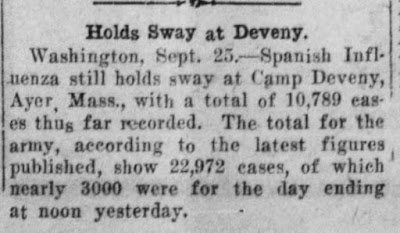

In September 1918, the second wave of pandemic flu emerged at Camp Devens, a U.S. Army training camp just outside of Boston, and at a naval facility in Boston. This wave was brutal and peaked in the U.S. from September through November. More than 100,000 Americans died during October alone. The third and final wave began in early 1919 and ran through spring, causing yet more illness and death. While serious, this wave was not as lethal as the second wave. The flu pandemic in the U.S. finally subsided in the summer of 1919, leaving decimated families and communities to pick up the pieces.

You may recall

from the McKinley school centenary, that the school building became a hospital for flu patients, and we will follow the headlines this fall to see how Salemites met the disease, treated it, altered social and economic patterns in public health actions, and grieved for those who died from it. At this time, in September, Salemites were isolated from the disease, and it was for the moment a distant story about other people and other places. But it was likely the railroads, as well as the movements of soldiers, would provide mobility for infected people to travel and spread the disease, and it seemed sure to appear here sometime.

1 comment:

With COVID-19 spreading, some are pointing again to this Smithsonian piece, "How the Horrific 1918 Flu Spread Across America."

The author's own research on the origin is interesting:

"Although some researchers argue that the 1918 pandemic began elsewhere, in France in 1916 or China and Vietnam in 1917, many other studies indicate a U.S. origin. The Australian immunologist and Nobel laureate Macfarlane Burnet, who spent most of his career studying influenza, concluded the evidence was “strongly suggestive” that the disease started in the United States and spread to France with “the arrival of American troops.” Camp Funston had long been considered as the site where the pandemic started until my historical research, published in 2004, pointed to an earlier outbreak in Haskell County [Kansas in early 1918]."

This is not what interests people today, however.

"The killing created its own horrors. Governments aggravated them, partly because of the war. For instance, the U.S. military took roughly half of all physicians under 45—and most of the best ones.

What proved even more deadly was the government policy toward the truth....while influenza bled into American life, public health officials, determined to keep morale up, began to lie....

...in my view, the most important lesson from 1918 is to tell the truth."

Post a Comment