|

| morning paper, February 24th, 1920 |

A year before, the papers had small notice about Beatrice Cannady visiting Salem to lobby at the Legislature for a civil rights law.

|

| Morning paper, February 3rd, 1919 |

|

| Afternoon paper, February 4th, 1919 |

|

| January 1st, 1920 |

|

| "Lady waitresses" - February 19th, 1920 |

From the morning paper on February 24th, 1920 (clip at top):

The sign in the window of the Blue Bird cafe which announces that only white persons will be served there is reported to have caused a small commotion as a result of which H. A. Bost, a negro, was arrested. He was freed under bond of $10 as his case could not be heard on the holiday.

Mrs. R. C. Cook, a waitress in the cafe, complained that Bost had made a disturbance and applied to her a vile epithet when she did not wait on him. When she pointed to the offending sign Bost tore it down. Officer W. J. White responded to the summons and arrested the man. Bost admitted to Night Sergeant Elmer White that he had torn down the sign but complained of the general determination against negroes in hotels and restaurants. He will appear before Judge Race this morning.

|

| Afternoon, Feb 23, 1920 |

police were awaiting the outcome of a rumored threat in colored circles that one of the negros "carries a fawty-faw and is going gunnin' as a result of an uprising and disturbance Sunday night in the Blue Bird Cafe....The court resolved the case very unfavorably for Bost.

[Cook] told police that Bost had entered the restaurant and demanded service. When she pointed to a sign in the window that whites only are accomodated she said that Bost in a furious rage tore the sign down and called her a vile name....

Bost admitted to Night Sergeant Elmer White that he tore down the sign and said "there ain't no place a colored gentleman can eat, and they won't even let 'em sleep any more," he guessed....

He was fined $20, and it appears he may have chosen a 10-day prison term instead.

That's a harsh penalty for tearing down a sign and, let's just assume as true, uttering one or more "vile names" in anger. It is also possible Cook, and even "witnesses," lied to embellish her case. Law enforcement and popular mobs supported the grievances of white women, and these she-said, he-said cases sometimes escalated to lynching. Bost would have known he was in special danger. (Though it was not motivated by race, remember the lynching in Centralia in November of 1919.)

|

| Morning, February 28th, 1920 |

|

| Afternoon, February 28th, 1920 |

About Bost there should be more to say, but he disappears. Maybe more research will turn up something on him. The narrative in the papers is not fair to him, flattening him out as a type rather than a full subject and agent.

* In James Loewen's database on "Sundown Towns," Salem is listed, but the documentation is slim. Mostly the evidence is anecdotal, so it was helpful to find something better documented.

Previously see:

- "100 Years ago The Birth of a Nation "took Salem by Storm"

- "Don't Forget about the Exclusion Laws in the Newly Restored Oregon Constitution"

- "New Book on Salem Clique needs more on Slavery"

- "The Exclusionary City in 1926"

- "When Minstrelsy was a Central Part of Civic Culture"

- "Guidance of Youth and the Ideology of Pioneer Mother Monuments"

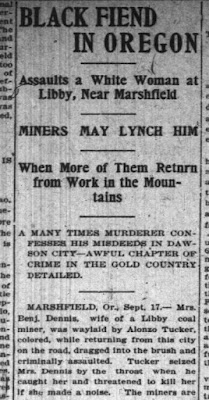

The Oregonian has a piece about "the only documented racial lynching in Oregon history." As it was nearly 20 years old in 1920, I'm not sure how directly relevant it is here, as even from far away, the 1919 race riots would have been more immediately terrifying.

But the lynching is background context nonetheless.

The Journal seems to have had a more direct correspondent, and the Statesman published "old news," the next morning. The clips here are flipped by publishing date, therefore, to give the narrative order right.

|

| September 19th, 1902 |

|

| September 18th, 1902 |

1 comment:

(Added clips on the 1902 Marshfield lynching.)

Post a Comment